Helen Atkinson reflects on how writing Morning Pages has helped her through changing jobs, studying part-time for her MA and surviving a pandemic.

For the past two years I have written (almost) every day. Mostly in a journal (though sometimes on my laptop), mostly a page long (though it can be as short as a few phrases, or a multi-page scrawl), mostly in the morning (but often in the afternoon or evening too).

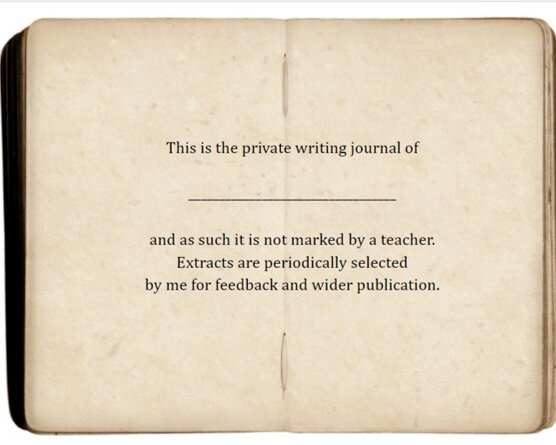

I have been following the principle of Morning Pages, though, as you’ll see above – I am no great respecter of rules. The phrase was coined by Dorothea Brandt in 1934 and later reinvented by creativity guru Julia Cameron and technically they are three pages of stream of consciousness writing done first thing in the morning. Like the ‘free writing’ that many of us will have done to stimulate writing with our classes, they are personal, not to be shared, and Cameron claims that they are designed to ‘clarify, comfort, cajole, prioritize and synchronize the day at hand.’ Morning Pages are not fitted to an audience or purpose, they fit no mark scheme, and no planning grid. They are simply words, spilled out onto a page.

I was first introduced to the practice by writer and lecturer, Peggy Riley. Peggy’s ethos is that Morning Pages can be whatever we need them to be, to support our creativity and our wellbeing. At the beginning of a part time MA in Creative Writing, I needed the commitment to daily writing in order to guard against the inevitable takeover of planning, preparation and marking. I wrote on my short 10-minute train journey to school, documenting the landscape, the weather, the other commuters and my own worries and hopes for the day ahead. Much of the writing was just a release of feelings but some words and phrases were recycled into longer pieces of ‘proper’ writing at a later date. Most importantly, the pages allowed me to process my unhappiness in my job. They gave me the clarity and courage I needed to leave.

Morning Pages then bumped and scrawled their way on the bus to a temporary teaching job. Their soothing repetition helped me to settle in and provided an outlet for my thoughts as I met new students and colleagues, and began to teach new texts. Morning Pages could be about the lashing of rain on the bus windows or unformed reflections on a poem.

Just a few weeks later, the first national UK lockdown began and, like many teachers up and down the country, I made the transition to online teaching. Beginning my days with Morning Pages, helped me to make sense of the chaos in both the wider world and the little room where I was teaching lessons into a laptop screen. Fearful of the days blurring into one another, I began counting them in Morning Pages that untangled news reports and statistics, provided fictional escapes, and charted the development of the seagull chicks on the roof next door.

Daily writing continues to help me balance my own writing with a rekindled love of teaching English. Sometimes, my Morning Pages are a free-form to do list or statement of intent, sometimes a draft zero of ideas, sometimes a wailed splutter onto the page. At times teaching pushes its way in, at others, it is writing just for myself. I let the pages be what they need to be on any given day. But some things are certain. I am more reflective because of Morning Pages, more secure in my own practice, both as a teacher and a writer, and a lot more resilient too.