Secondary English teacher Theresa Gooda explains why writing frames and rigid structures have limited scope to help develop ‘real’ writers.

The Great Sphinx, surrounded by scaffolding, during restoration work in 1990 Barry Iverson / The LIFE Images Collection / Getty

I was fortunate to visit the pyramids at Giza and the Sphinx many years ago. It was the trip of a lifetime to see one of the wonders of the world. I must confess to being disappointed, though, that the Sphinx was undergoing a process of restoration at the time, and was mostly hidden behind scaffolding frames. I lamented that I couldn't capture the perfect shot of this magnificent sculpture. My own photographs are more suggestive of a building site than one of the world’s largest and most famous monuments.

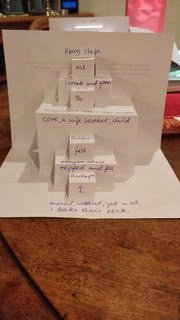

Writing is another wonder of our world. It is a complex process that draws on all sorts of writer’s resources, requiring far deeper foundations than the end result of squiggles on a page might suggest. Enabling students to create texts involves tapping into their knowledge of all sorts of linguistic structures and patterns via multiple routes and genres. Who wouldn't be grateful for a helping hand? It is no surprise that novice (and experienced) writers welcome guidance, pointers, and frameworks along the way, seeking a leg-up wherever it is offered.

This perhaps explains why writing frames for genre writing and PEE (POINT, EVIDENCE, EXPLAIN) and PETAL (POINT, EVIDENCE, TECHNIQUE, ANALYSIS, LINK) for written responses to reading can, in some circumstances, be attractive for novice writers and teachers of writing. But it is worth remembering that they remain scaffolding outside the ‘building’ of the writing. They do not amount to an end product. We definitely don't want to ‘see’ them. Such scaffolding needs to be removed, as soon as possible, so that it doesn't spoil the picture.

PEE, PETAL and their other, sometimes elaborate incarnations may, if not used judiciously, ultimately end up spoiling the writing. As soon as writing becomes formulaic, it ceases to be a wonder. The helping hand becomes the very thing that ends up restricting students. If paragraph after paragraph of writing follows an identical pattern, there is no opportunity for novelty or surprise, no space for originality or flair - in critical or creative writing. As Peter Thomas writes, frameworks such as these ‘support a discipline of Lego Linguistics but do little to develop a humane version of the English curriculum or improve students’ real writing.’ Simon Gibbons also notes the resulting marginalisation of student choice, voice and personal response in Death by PEEL.

Perhaps the answer is to provide those supports when they are necessary for ‘stuck’ writers, but to remove them at an early stage; and to encourage students to see PETAL and its counterparts not as rigid but as amorphous. Not only do the petals of even a single flower assume many variegated shapes and forms, but individual petals can be scattered in the air as confetti, landing any which way, or being carried off by the wind.

Additionally, we have a responsibility to find multiple routes to support ‘stuck’ writers, by modelling different approaches, rather than restricting students to a single thoroughfare. This will allow teachers to open up the creative possibilities of writing, including critical writing, rather than narrowing them down to a single way. Writing requires careful induction into a community of practice, ‘borrowing the robes’ of writers that have gone before by exploring plenty of texts and trying out their rhythms. It is liberating for students to find their own patterns within texts and explore them, rather than particular patterns being imposed on them.

The English & Media Centre have long been advocates of this kind of more playful, exploratory approach to writing, reflected in such resources as Just Write, an illustrated workbook for KS3 students designed to ‘harness pupils’ enthusiasm for writing and to develop their writing “muscles” ’.

Like the NWP, the emphasis is on empowering students to reach a point where they can trust that, as writers, they can afford to take a risk with writing.

Writing is, after all, a risky business.

To return to the poor Sphinx, I have no doubt that some sort of scaffolding structure was necessary while the Egyptian colossus was first being carved in limestone 4500 years ago, but it did seem a shame that I had to see it that way, with its true power and beauty hidden.

Let's not keep our classroom writers hidden beneath confining frames, stuck on a building site, but allow them to carve out their own wonderful forms.