Secondary English teacher Theresa Gooda reflects on why poetry is such a powerful way of teaching writing.

As a younger teacher, I remember being quite terrified of teaching poetry. I think I’d always found it difficult at school at university, and, until a few years ago, I certainly wouldn’t have dreamed of sitting down to read a collection of poetry. Now I’m as likely to pick up a book of poetry as I am a novel when I’m gathering together reading for, say, a holiday, but it has taken decades to reach that point.

Gradually, I came to enjoy some poets and poetry, probably through coming to know individual poems well from teaching them. Slowly it became pleasurable rather than a chore. For the classroom, I like that often there is a small amount of text so it feels manageable, but that words on the page are much richer and more playful when part of a poem.

It’s rewarding to use poetry as part of an English lesson. A student ‘getting’ a poem is great, but even better the other way round: I love it most when a poem ‘gets’ a student.

But I think that what I really enjoy is the way poems ‘teach’. I don’t mean that they do so in any moralistic way. I simply mean the way that they ‘teach’ writing, without me having to do very much at all.

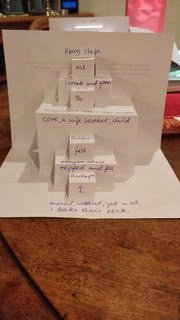

Poems often offer structures and ideas that students can borrow and try on for size. Giving a student a copy of Great Expectations and expecting them to write like Dickens is more than intimidating. Sharing a copy of ‘This Is Just to Say’ by William Carlos Williams gives students a form they can emulate and be inspired by. I rarely ask students to write ‘poetry’ as a result of reading poetry, but their writing will be richer for reading it and experimenting.

Although it was published forty years ago, I’ve only recently come across Richard Hugo’s ‘The Triggering Town ', a collection of lectures and essays on poetry and writing. It’s billed as being full of excellent advice for beginning writers, and, while I’m always a little bit wary of ‘advice for writers’ lest it become too formulaic, much of Hugo’s advice is heartening and relates to exploring process rather than outcomes.

In school we seem obsessed with the outcomes, and spend a great deal of time telling students ‘how’ to write. Yet so much happens during the act of writing that it’s almost impossible to be told ‘how’ to do it: you simply have to ‘do’. As Hugo puts it, ‘ultimately the most important things a poet will learn about writing are from himself in the process’ (1982, p. 33).

Hugo begins with a disclaimer. He isn’t hoping to teach readers how to write, but ‘how to teach yourself to write’ (1982, p. 3). He is speaking to ‘those of us who find life bewildering and who don’t know what things mean’ (ibid. P. 4), suggesting that it is through writing that we might at least get closer to some understanding. Life is bewildering for most teenagers moving through secondary school, and writing offers a negotiating tool.

Once you have a certain amount of technique, Hugo argues, ‘you can forget it in the act of writing.’ This is the stage that we want our students to reach as writers: not to be stuck on the steps before, forcing a sentence to begin with a fronted adverbial, or including a simile because the teacher told them to.

But, the idea that most resonated was this one:

When we are told in dozens of insidious ways that our lives don’t matter, we may be forced to insist, often far too loudly, that they do. A creative-writing class may be one of the last places you can go where your life still matters. (Hugo, 1982, p. 65)

Writing matters, because the lives of our students matter.

References:

Hugo, R. (1982) The Triggering Town. New York: Norton.